The Amiga Workbench stands as one of computing’s most innovative yet overlooked operating systems, revolutionizing how users interacted with personal computers during the late 1980s and early 1990s.

🖥️ The Dawn of a Revolutionary Interface

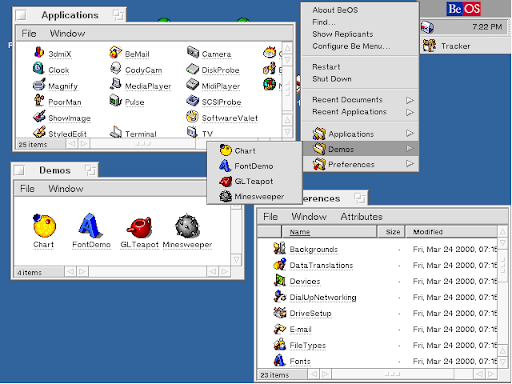

When Commodore released the Amiga 1000 in 1985, it introduced something remarkable to the computing world: Workbench, a graphical user interface that would redefine what users expected from their machines. While other computers struggled with command-line interfaces and primitive graphics, Amiga Workbench presented a colorful, intuitive environment that felt decades ahead of its time.

The original Workbench operated on just 256KB of RAM, yet managed to deliver a multitasking experience that put contemporary systems to shame. This efficiency wasn’t accidental—it was the result of brilliant engineering by a team that understood both hardware limitations and user needs. The system utilized a unique approach called “preemptive multitasking,” allowing multiple applications to run simultaneously without one program hogging all the resources.

Why Workbench Changed Everything

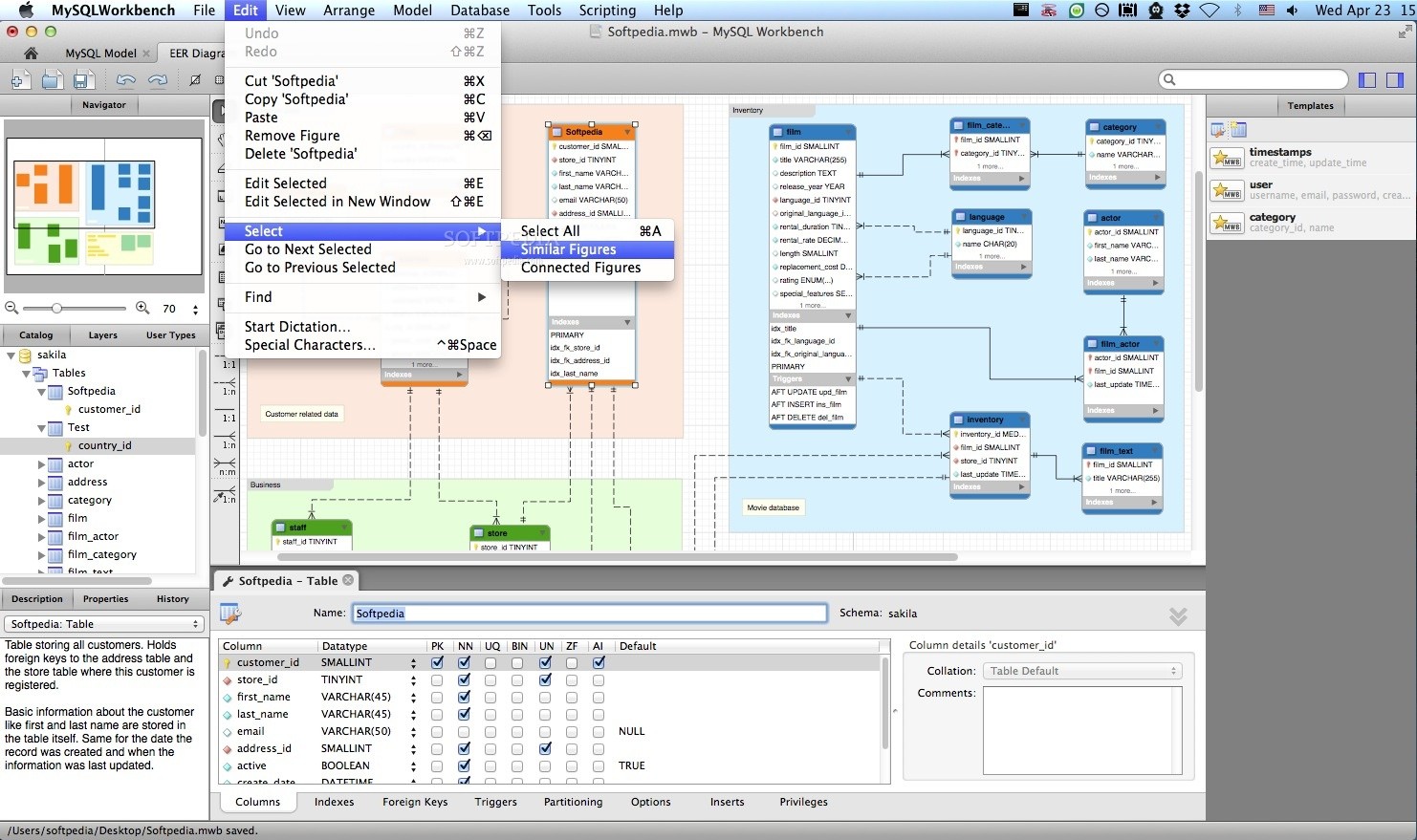

Before Workbench, most personal computer users faced steep learning curves. DOS commands required memorization, and making mistakes could result in lost data or system crashes. Amiga’s approach democratized computing by presenting information visually. Icons represented programs and files, windows could be resized and moved, and menus provided discoverable options.

The interface featured a distinctive two-tone blue and orange color scheme that became iconic. The top menu bar, called the “Workbench screen,” remained accessible even when applications ran in their own windows. This design philosophy influenced countless operating systems that followed, though few historians acknowledge Amiga’s pioneering role.

Technical Marvels Under the Hood

What made Workbench truly special was its integration with the Amiga’s custom chipset. The system featured three specialized coprocessors—Agnus, Denise, and Paula—that handled graphics, video, and audio independently from the main CPU. This architecture allowed Workbench to display up to 4,096 colors simultaneously while playing four-channel stereo sound, capabilities that wouldn’t become standard on PCs for nearly a decade.

The operating system’s kernel, called Exec, managed memory and task scheduling with remarkable sophistication. Unlike cooperative multitasking systems where poorly written programs could freeze the entire computer, Exec’s preemptive approach ensured system stability. Applications received time slices automatically, preventing any single program from monopolizing processor resources.

The Evolution Through Workbench Versions

Workbench underwent significant transformations throughout its lifespan, each version adding features while maintaining backward compatibility—a commitment that endeared it to developers and users alike.

Workbench 1.x: The Foundation Years

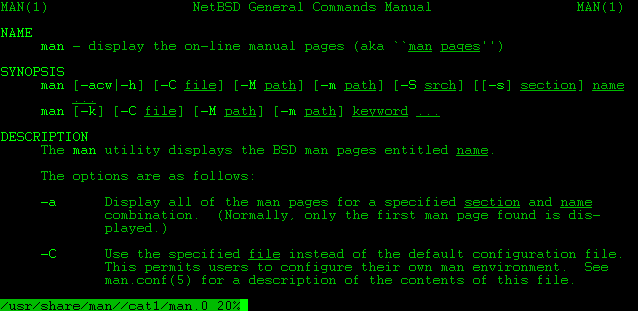

The initial releases (1.0 through 1.3) established the core principles. Version 1.0 shipped on a single floppy disk and included basic file management, preferences configuration, and essential utilities. Version 1.2 introduced the Amiga Command Line Interface (CLI), later renamed AmigaShell, giving power users access to sophisticated scripting capabilities.

Workbench 1.3, released in 1988, refined the interface and added support for new hardware. The system could now handle hard drives more efficiently, and memory management improved dramatically. These early versions proved that graphical interfaces didn’t require sacrificing power or flexibility.

Workbench 2.x: Maturity and Refinement

The release of Workbench 2.0 in 1990 marked a watershed moment. The interface received a complete visual overhaul with three-dimensional beveled buttons and a more sophisticated color palette. More importantly, the underlying operating system gained new capabilities that positioned Amiga as a serious professional platform.

Key improvements included:

- Expanded memory support beyond the original 512KB limitation

- Advanced graphics modes supporting higher resolutions

- Improved font rendering with scalable outline fonts

- Enhanced printer support and driver architecture

- Better networking capabilities through AmigaTCP/IP

Workbench 2.1 addressed bugs and added localization support, making the Amiga truly international. The system could display different languages, keyboard layouts, and regional preferences—features that seem obvious today but were revolutionary in 1991.

Workbench 3.x: The Golden Age

Workbench 3.0, introduced in 1992, represented the platform’s peak. The Advanced Graphics Architecture (AGA) chipset enabled 256-color displays from a palette of 16.8 million colors. The interface could now rival professional Unix workstations costing ten times more.

Version 3.1 became the most stable and widely adopted Workbench release. It included DataTypes, a system that allowed applications to handle various file formats without built-in support. If you installed a JPEG datatype, any program could display JPEG images—a precursor to modern plugin architectures.

🎨 The Creative Professional’s Paradise

While gamers loved the Amiga for its superior graphics and sound, professionals recognized Workbench as an ideal creative platform. Video production facilities adopted Amigas for their rendering and editing capabilities. The Video Toaster, a breakthrough hardware/software combination running on Workbench, appeared in television studios worldwide.

Desktop publishing flourished on the platform. Professional Page, PageStream, and other applications leveraged Workbench’s graphics capabilities to produce print-quality output. Musicians embraced the system’s low-latency audio processing—many electronic music pioneers composed on Amigas equipped with software like OctaMED and ProTracker.

Gaming Beyond Console Capabilities

Workbench’s multitasking nature created unique gaming possibilities. Players could run music trackers in the background while gaming, switch between applications without rebooting, and even chat on bulletin board systems while waiting for levels to load. These conveniences seem mundane now but were science fiction on competing platforms.

Classic titles like Lemmings, Sensible Soccer, and the Monkey Island series showcased what Workbench-equipped Amigas could achieve. The operating system’s efficient memory management meant games could access maximum RAM, while the custom chipset delivered smooth scrolling and sprite handling that PC clones couldn’t match.

The Community That Refused to Fade

Even after Commodore’s bankruptcy in 1994, the Amiga community persevered. Enthusiasts continued developing software, creating new Workbench themes, and pushing the hardware beyond original specifications. This dedication spawned innovations that influenced modern computing in surprising ways.

The demo scene—artists and programmers creating audiovisual presentations—thrived on Amiga. These demos pushed Workbench and the underlying hardware to impossible limits, achieving effects that shouldn’t have been feasible. Techniques developed by demo coders later appeared in video games, compression algorithms, and graphics software across all platforms.

Open Source Resurrection Efforts

Modern projects like AROS (Amiga Research Operating System) and MorphOS keep the Workbench spirit alive. AROS provides a free, open-source implementation compatible with original Workbench software, running on modern x86 and ARM hardware. Developers can experience authentic Amiga computing without vintage equipment.

UAE (Unix Amiga Emulator), later renamed WinUAE on Windows, allows perfect emulation of various Amiga models. These emulators preserve computing history while enabling new generations to discover Workbench’s elegance. Enthusiasts have created distributions bundling emulators with legal software, making exploration accessible to anyone curious about this forgotten chapter.

⚡ Technical Innovations That Shaped Modern Computing

Many features users take for granted today originated or matured on Workbench. Understanding these contributions reveals how significantly Amiga influenced contemporary operating systems.

Preemptive Multitasking

While Unix systems offered multitasking, they remained expensive and complex. Workbench brought preemptive multitasking to affordable home computers, proving that sophisticated scheduling didn’t require mainframe-class hardware. Windows wouldn’t achieve true preemptive multitasking until Windows NT in 1993, and consumer versions waited until Windows 95.

Plug and Play Hardware Recognition

AutoConfig, Amiga’s expansion card detection system, automatically identified and configured new hardware. Users simply inserted expansion cards, and Workbench recognized them without driver installation or configuration files. This concept wouldn’t appear on PCs until the Plug and Play specification emerged in the mid-1990s.

Advanced Audio Architecture

Paula, the Amiga’s audio chip, offered four independent 8-bit PCM channels with stereo panning. Workbench integrated audio system-wide—applications could play sounds simultaneously without conflicts. This audio mixing capability, managed by the operating system, predated Windows DirectSound by nearly a decade.

🔍 Why Workbench Disappeared From Mainstream Consciousness

Despite technical superiority, Amiga and Workbench faded from prominence. Understanding this decline offers lessons about technology markets, corporate strategy, and the disconnect between technical excellence and commercial success.

Corporate Mismanagement

Commodore’s leadership failed to capitalize on the Amiga’s advantages. Marketing emphasized gaming rather than professional applications, limiting the platform’s perceived seriousness. While Apple positioned Macintosh as creative tools and IBM targeted businesses, Amiga occupied uncertain middle ground.

The company also struggled with product strategy. Instead of maintaining a focused lineup, Commodore released numerous models with confusing specifications and overlapping capabilities. This fragmentation diluted brand identity and frustrated consumers trying to choose appropriate systems.

The Wintel Juggernaut

By the mid-1990s, PC clones running Windows had achieved economies of scale that Amiga couldn’t match. Volume production drove prices down while performance increased. Even though Workbench offered superior multitasking and efficiency, Windows 95’s massive marketing campaign and broad software support proved insurmountable.

The gaming market shifted decisively toward PCs and dedicated consoles. As VGA graphics improved and sound cards became standard, PCs eliminated the Amiga’s technical advantages. Meanwhile, Sony PlayStation and Sega Saturn offered gaming experiences that surpassed Amiga capabilities at comparable prices.

Lessons From a Forgotten Operating System

Workbench’s story provides valuable insights for technology professionals, historians, and enthusiasts. Technical superiority alone doesn’t guarantee market success—business execution, timing, and ecosystem development matter equally.

The platform demonstrated that elegant design and efficient resource utilization can deliver exceptional user experiences even with limited hardware. Modern developers, often working with abundant memory and processing power, could learn from Workbench programmers who achieved remarkable results within tight constraints.

The Importance of Community

Perhaps Workbench’s greatest legacy is the passionate community it fostered. Decades after commercial viability ended, enthusiasts continue preserving, documenting, and extending the platform. This dedication ensures that future generations can study and appreciate this remarkable chapter in computing history.

Online repositories archive thousands of Workbench applications, utilities, and games. Websites like Aminet continue hosting software, with uploads still occurring regularly. This community-driven preservation stands as testament to the platform’s enduring impact on those who experienced it.

🌟 Rediscovering Workbench in the Modern Era

Contemporary interest in retro computing has sparked renewed Workbench appreciation. YouTube channels document restoration projects, programming tutorials teach AmigaOS development, and retro gaming events feature Amiga competitions. This renaissance introduces new audiences to innovations they might otherwise never encounter.

Collectors seek original hardware, with pristine Amiga 500s and 1200s commanding premium prices. However, emulation provides accessible alternatives for those wanting authentic experiences without vintage equipment investment. Modern computers can run multiple Workbench versions simultaneously, enabling comparative studies and nostalgic exploration.

Educational Value for Current Developers

Studying Workbench benefits programmers working with embedded systems, mobile devices, and resource-constrained environments. The techniques Amiga developers employed—efficient memory management, hardware acceleration, and optimized assembly code—remain relevant when every byte and clock cycle matters.

The operating system’s design patterns influenced countless projects. Examining Workbench architecture reveals elegant solutions to problems that modern developers still face, often solved with far more complexity than necessary.

The Enduring Spirit of Innovation

Amiga Workbench represents more than forgotten software—it embodies a philosophy that prioritized user experience, technical excellence, and creative possibility. The platform emerged during computing’s formative years when experimentation flourished and conventions hadn’t yet calcified.

Today’s computing landscape, dominated by three major operating systems and standardized interfaces, sometimes feels constrained compared to the diversity of Workbench’s era. Reflecting on this history reminds us that alternative approaches exist, that technical decisions involve tradeoffs, and that mainstream adoption doesn’t always correlate with innovation quality.

The mysteries of Amiga Workbench, once revealed, demonstrate that computing history contains numerous remarkable achievements overshadowed by commercial outcomes. Preserving and studying these forgotten chapters enriches our understanding of technology’s evolution and inspires future innovations. The Workbench legacy lives on—in emulators, in community projects, in technical approaches that modern systems quietly adopted, and in the memories of those fortunate enough to experience computing’s most elegant underdog. 🚀

Toni Santos is a visual historian and creative artisan whose work channels the bold spirit of the steam-powered era—a time when imagination, mechanics, and ambition converged to reshape the modern world. Through richly detailed visual narratives and handcrafted design, Toni celebrates the legacy of steam innovation as both an artistic and technological revolution.

Driven by a passion for mechanical aesthetics, forgotten inventions, and industrial-age ingenuity, Toni reimagines the world of steam through illustrations, tactile artifacts, and storytelling that capture the poetry of pressure, motion, and invention. From piston-driven engines to brass-detailed diagrams, each piece reveals how steam wasn’t just power—it was promise.

With a background in visual design and historical research, Toni brings a craftsman’s eye and a dreamer’s heart to the stories of tinkerers, inventors, and visionaries who shaped the 19th century. His work doesn’t merely document machines—it honors the culture, courage, and creativity that drove a world to reimagine itself through gears, valves, and vapor.

As the creative voice behind Vizovex, Toni shares curated articles, reconstructed blueprints, and visual interpretations that bring this industrial past to life. His collections serve as a tribute to:

The elegance of steam-era design and innovation

The human stories behind great mechanical feats

The aesthetic beauty found in function and form

The echo of invention in today’s creative world

Whether you’re a history lover, a fan of steampunk, or an admirer of antique technology, Toni welcomes you into a world where art and machinery fuse, one cog, one drawing, one rediscovered marvel at a time.